My mom was one of the first black children to be adopted by a white family in British Columbia. In 1969, the Vancouver Sun featured her in an article headed “Negro Orphans in Demand,” describing her as “Just One of the Family.” The story itself presents a bait and switch: she’s first described as a “problem child,” but then it comes out that the only issue she has is being too cute; the joke is that you’d assume that, as a black child, she would be “a problem.” In 1969, this was thought of as accepting.

Listen to an audio version of this story

For more Walrus audio, subscribe to AMI-audio podcasts on iTunes.

Most black people have far worse stories. As a kid in Oakville, Ontario, my dad ducked rocks thrown by his classmates after he moved with his family to a white neighbourhood. I was never short of these stories growing up. They were presented alongside the ones all black children are told about Rosa Parks, Harriet Tubman, Emmett Till, Martin Luther King Jr., and Viola Desmond. Stories of the people you’re supposed to live up to. People who share a culture.

I had to experience that culture second-hand. Unlike my parents, I was just the lone middle-class black kid at a good school, not long before a black man became president of the United States. I was so far removed from the culture they belonged to, it felt like a lie to say I was “really” black. I wasn’t pelted with rocks. I wasn’t sprayed with firehoses. I didn’t even sound like the black people I saw on TV. Instead, I’d look in the mirror and know that the only thing black about me was my skin. I was halfway between each group: superficially of both, but realistically, of neither.

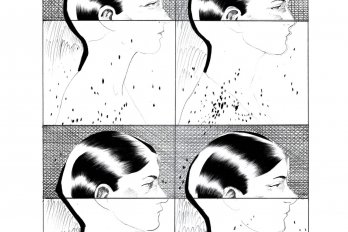

So I was terrified of haircuts. Black hair has survived cultural integration; it’s a different material than white hair, and you need to go to people who know how to work it. We’d take the hour drive, and I’d go to black hairdressers and sit in the chair, staring in the mirror, terrified to open my mouth. I didn’t want to miss a reference I should know. I didn’t want to reveal what I imagined everyone in the room knew: I was a cultural failure.

That fear made me spend the early 2000s studying Kunta Kinte as he grimaced in the movie Roots, lashed to a post, refusing to give up his name. I memorized Kanye West lyrics, then pretended I’d always hated him when my cousin laughed and told me that was “white people rap.” I read The Autobiography of Malcolm X for a sixth-grade report, telling my teacher I could finish a book that turned out to be twice as long as any of the others chosen. I said it was because I loved reading. In truth, it was because staying up late every night, struggling to keep to the chapter schedule I’d set for myself, was a form of suffering I had invented. In high school, a white friend with a tougher home life and far better knowledge of hip hop told me he was more black than I was. I fought him on it. At the same time, we both knew he was right.

At thirteen, I went to New York to see my black aunts, uncles, and cousins. They had experiences, knowledge, and patterns of speech that granted them entry into the club I still didn’t know how to join.

I said hi to my cousins. They laughed a little when they spoke to me. I smiled back awkwardly.

They asked, “Why do you talk so white?”

I didn’t speak much after that.

Back in 1947, psychologists Kenneth and Mamie Clark asked children to look at dolls that were identical except for their skin colour, and then decide which ones were “nice” and which were “bad.” Nearly all the children, whose skin tone ranged from light to dark, identified the black doll as “bad.” This experiment showed, among other things, the negative effects segregation can have on self-confidence and self-perception. We’ve moved past blatant segregation now; my mom was adopted into a white family, and my dad eventually stopped having to duck rocks. But we still see race. For my white friends, being white was a fact it was what they were supposed to be. My being white signified a failure. I was born with black skin, but had done nothing to deserve it.

I still walk into barbershops feeling like a trespasser in my own skin. I sit uncomfortably, as if just breathing is a cultural appropriation. I speak and am reminded that the people we are, the people we appear to be, and the people we identify with can be vastly, painfully different. Sometimes they go together. Sometimes they don’t. Sometimes, we’re orphans.