Halfway through Steven Heighton’s The Nightingale Won’t Let You Sleep, I went online in search of Famagusta and its suburb, Varosha, the once-thriving resort town at the centre of the novel. The site was abandoned in 1974, when the UN partitioned the Republic of Cyprus into the Greek south and Turkish north. Varosha lies in the hinterland between the two regions and is mostly fenced off from the public.

I didn’t find much to look at online. Varosha is inaccessible via Google Street View, although a Daily Mail article featured a suite of drone shots depicting high rises covered in vegetation. The best images, though, are those that Heighton conjures with words. “Varosha,” writes Heighton, is “like a place in a lucid dream, both solid and spectral.” It is a terrestrial Atlantis: a lost city where formerly gracious courtyards have been reclaimed by rabbits, birds, and snakes.

There are human inhabitants too. Heighton depicts a community of outsiders—most of them Greeks—who live secretly among the ruins. This tiny village, with its rivalries and shifting balance of power, is a microcosm of the outside world, one that, in Heighton’s vision, includes war-torn Afghanistan, post-crisis Greece, and the darkening landscape of Erdoğan’s Turkey. The Nightingale is a novel about big, global forces and small, intimate moments. Politics, for Heighton, happens on all levels: the international and the interpersonal.

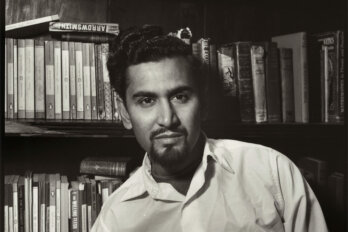

In North America today, there are few novelists like Heighton, an award-winning poet and essayist who also writes carefully plotted literary adventures—the kind in which disparate people come together in farflung places. His 2006 novel Afterlands chronicles the doomed Polaris expedition to the North Pole and the messy, guilt-ridden lives of the survivors. Every Lost Country (2010) features four people on a mountain-climbing expedition; Chinese authorities arrest two of them along with a group of fleeing Tibetan refugees. The novel goes on to depict a prison break and a perilous journey to Nepal. Heighton’s narratives often move from place to place. His writing harkens to an older moment, when travel—by steam train, say, or ocean liner—was expensive, and literature offered an affordable way to explore the world.

Heighton is often compared to Joseph Conrad. It’s better, though, to say that he inherited a post-Conrad tradition, which extends from E. M. Forster to Graham Greene to John le Carré. These novelists were—and in le Carré’s case still are—literary practitioners and epic storytellers. They write about human psychology but also migration, authoritarianism, warfare, nationalism, and coups. They share a sense that you can’t understand humans separately from the world. This approach stands in contrast with much North American fiction, which often defines politics narrowly in terms of inter-relationships and identity. (There’s nothing wrong with identity politics, but geopolitics matter too.)

The protagonist of Nightingale is Elias Trifannis, a brawny Greek Canadian who stumbles unaware into the secret Varosha community. Elias is an Afghanistan veteran whose tour of duty ended with a gruesome massacre in an olive grove, for which he considers himself a war criminal. While battling PTSD in a Cyprus hospital, he meets Eylül Sahin, a Turkish journalist with dark eyes that “flash with startling vehemence.” Romantic relationships between Turks and Greeks are verboten in Cyprus: the violent partition of the island has solidified ethnic divisions. While flirting with Eylül at a bar, Elias notices a group of Turkish soldiers eyeing him “with that ancient faculty of minute discernment found in any region where ethnic groups collide, where the borders are disputed, where the grievances have grown roots.”

Elias and Eylül’s first—and, as it turns out, last—meeting ends with a brief sexual encounter on a public beach. The moment is charged but gloomy. Elias is dangerously sleep deprived and hungry for a kind of intimacy his tired body can’t handle. With Eylül, he’s barely hard, but she’s patient with him, like a nurse attending a wounded soldier, which is what he is. Moments later, the couple is accosted by the men from the bar. The conflict escalates, Eylül is shot down, and Elias escapes into the Varosha dead zone, where he takes refuge among the lost people.

Erkan Kaya, a cheerily corrupt Turkish colonial at Varosha’s outpost, is charged with ensuring that this travesty doesn’t become a public-relations fiasco. He concocts a story in which Elias is the aggressor, and the men who shot Eylül—his soldiers—intervened only to help her. It’s not just army secrets that Kaya keeps, though. For years, he’s protected the dead zone’s hidden residents, trading goods with them and shielding them from public scrutiny.

But Kaya’s position is becoming untenable. His busybody underling, Aydin Polat, has ventured into the dead zone and found proof of people living there—evidence he plans to expose. Eylül is in a coma at the local hospital; if she wakes and tells her story, Kaya’s version may no longer stand. And then there’s the problem of Elias, the missing Canadian who’s disappeared into the heart of Varosha. What happens if he re-emerges?

These details are the pegs on which Heighton hangs his story, but the book is much more than plot. Heighton is as competent with sentences as he is with storylines. Unlike other plot-oriented writers, he doesn’t treat words as afterthoughts. In his prose, a copse of olive trees is “burled and gnarled as ginger root” and the insides of a decaying buildings evoke “shockingly exposed viscera.” The Nightingale includes a digression about the most evocative locutions in each language. “Take the Turkish word for friend, arkadash,” writes Heighton, “an atrium of rich sounds, the last syllable lingering in a shhhh that extends the life of the utterance, delaying the silence to follow.”

The novel is full of beautiful asides like this. It’s also full of memorable characters, whose friendships are as fraught and rich as the word arkadash itself. In the dead zone, Elias encounters other refugees of violence and fate. His compatriots include Stratis, an embittered chauvinist with a tragic history who’s both protective and spiteful toward his fellow villagers; Roland, a former UN peacekeeper, who, like Elias, committed a heinous act in a moment of panic; and Ekaterini “Kaiti” Matsakis, a young mother of two who came to the dead zone fleeing heartbreak and bigotry.

Elias falls for Kaiti, and she for him. The second half of the novel charts the rhythms of their partnership: the heady narcotic of new love, the languid afternoons amid the ruins, and the way their relationship changes the dynamics of the tiny village. For some aging members, the presence of a young couple offers the dying community a chance at rejuvenation. For Stratis, though, it’s an insult: Elias has now fully insinuated himself into a world that isn’t his. (It’s possible to see a parallel here between Elias and Heighton. Heighton’s willingness to write about Greeks and Turks makes him vulnerable to accusations of “cultural appropriation,” a blunt charge sometimes levelled at writers who are interested in more than just themselves.)

Heighton is as attuned to the micro-politics of the village as to the macro-politics of Europe and the Middle East. His descriptions of the Afghanistan war invoke not just the violence but the way it induces people to do terrible things. And the novel includes a clever, politically resonant side plot involving Kaya and his officious subordinate, Polat. Kaya is a throwback to an older, more secular Turkey: He is a gentleman, epicurean, player of tennis, and seducer of women. Polat—the product of a militarized, authoritarian moment—is younger and angrier, a war hero who leads raids against Kurdish insurgents. His body is graceless but strong, like an assault rifle, and his visceral hatred for Greeks compels him to investigate the Varosha dead zone despite Kaya’s desperate attempts to stop him.

The Kaya-Polat narrative enables Heighton not only to advance the story but also to situate his book against the backdrop of Erdoğan’s Turkey and the tense, fractured culture of Cyprus. It is this larger, violent world from which the dead zone’s secret residents have fled. But, thanks to Polat, it crashes in anyway.

Like Varosha, The Nightingale is somehow of its time and outside of it. It’s grounded in its political moment but aloof from publishing-industry trends. Heighton could have tweaked The Nightingale to better market it to readers or literary juries. He might have given Elias the kind of family backstory—a foundry in Nova Scotia, a farm in Saskatchewan—that jibes with CanLit tropes. He could’ve strategically focused on identity, race, or masculinity, topics that are present in the book but only subtly.

Rather than homing in on a single theme, Heighton opts for a kind of narrative equilibrium. His focus is sometimes hermetic, sometimes global, and he balances violent passages with lyrical depictions of intimacy. In one scene, during a long afternoon with Kaiti, Elias suddenly finds himself paralyzed. “He can’t move. He doesn’t dare,” Heighton writes. “Time has snagged on something; but as soon as he budges, speaks, acts in any way—even breathes—it will start up again and sweep them on toward who knows what . . . most likely partings, endings.” For Heighton, there is no place that’s removed from history; there are only people who dream of living in such places.