A fter seven years of working for the students’ union at Ryerson University, Gilary Massa had a baby and went on maternity leave. Three months later, in December of 2015, she was fired without notice, and her employer replaced the unionized position with a non-unionized one.

Support for Massa mobilized through a Facebook campaign called “I Stand With Gilary.” The page helped coordinate meetings and petition signature blitzes. It coalesced anger from sympathetic individuals across Canada, and shared information about maternity leave and workers’ rights.

Then, in September 2016, the campaign ended abruptly—a legal settlement between Massa and her former employer had been reached. Some organizers said that Facebook was critical for this win: it acted as a ready-made tool for finding hundreds of others who then put pressure on the student union.

But organizing through Facebook also had its limits. During the campaign, several women contacted the group to ask for help navigating their own maternity-leave horror stories. The page administrators couldn’t offer much assistance, though: all of the group’s momentum fizzled the moment Massa’s settlement was reached. Facebook may have been instrumental in resolving this individual issue, but it wasn’t able to morph the fight into something broader.

A campaign needs a perfect narrative in order to succeed on Facebook: a problem, and a straightforward solution that people can rally around. But many campaigns—especially ones that focus on systemic issues—don’t fit this arc. Righting a wrong done to a woman on maternity leave is one thing, but achieving larger progressive goals, such as extending paid leave for new parents, or creating a national childcare plan, are other challenges altogether.

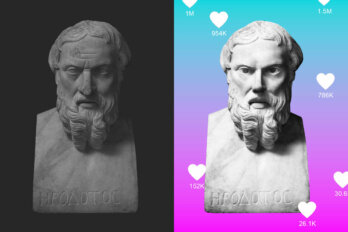

Facebook is now ubiquitous in the activist community, and people tend to go from one crisis to the next, liking, sharing, and clicking through a deluge of posts. But amid the chaos, they rarely evaluate whether or not this form of activism is working. Too often, it leads to progressives spending time and energy treating the symptoms of societal problems, while actively hurting their fights for the structural changes that could do the most good.

Facebook is a medium that is constantly looking backward: from the daily reminders of what you were doing last year, to a steady stream of reactions and “friend anniversaries.” The platform that promised to let us creep our high school classmates, our exes, and our acquaintances now holds years of our lives in its hands.

It makes for a strange location to organize social change. Nevertheless, Facebook is now the modern town square. Unlike a real town square, however, it mediates our interactions and filters everything to focus on each user’s specific wants and needs. Our friends appear more frequently if we engage with what they write, or if we scroll past their posts more slowly than others’. Ads are tailored to our Google search histories and identity data, or where we say we live.

We’ve been tricked into believing that Facebook is a neutral blank slate. This is a lie. Facebook is actually society’s most powerful driver of individualism. It recasts us to conceive of ourselves as being individual units within society instead of part of a collective group. Despite the platform’s promise of community, it can more often than not lead to splintering, and, when taken to the extreme, social isolation.

During political conversations on Facebook, things can quickly spin out, making common ground elusive or even impossible. When speaking with others on the platform, we aren’t physically in their presence—we remain in our heads. We attribute to and project things onto others, and body language is completely absent. Instead of taking the time to work through problems, it’s much easier to go for a stranger’s jugular during a disagreement. There is no need to reach a consensus, there are no useful outcomes from fights. Issues that ought to be momentary setbacks can quickly become conversation-enders; users can simply move on to the next item that appears on the feed.

Facebook also offers activists the feeling of contributing to social progress, while obscuring the fact that the platform cannot stand-in for real-life, on-the-ground organizing. It tricks us to think we’re taking action, when in reality, we aren’t. Take the election of Justin Trudeau: during the campaign, he made many progressive promises, such as for electoral reform. Many on the left—including traditional NDP supporters—turned to Facebook to promote this platform and tell others to strategically vote Liberal. But the “Real Change” that the Liberals promised is a far cry from what’s been delivered. Not long after election day, Trudeau’s promise for electoral reform was dropped, and there was no on-the-ground organizing that could hold his party to account.

D ave Bush is an editor for the union-focused news site RankandFile.ca, and is active in the campaign for a $15 minimum wage. Rank and File has leveraged Facebook to gather labour news from parts of Canada that rarely make headlines, and connect with workers to write about their own struggles. However, Bush is aware that these are the medium’s limits. “Facebook is deadly because people are no longer aware of its presence,” he says. He argues that progressive people need to see Facebook as a space to amplify voices, rather than as a site to organize.

The Fight for $15 campaign uses Facebook to post information, promote articles, troll employer organizations and, most importantly, show followers the kinds of events it’s engaged with in real life. It is these real-world activities—the petition signatures, rallies, meetings, and forums—that have helped build this campaign, Bush says. They are also what led to a surprising victory: the Ontario Liberals recently announced that they will be increasing the minimum wage to $15 in the coming years.

But, as we’ve seen with the federal Liberals and electoral reform, this win is not fully secured. Since the announcement, the Progressive Conservatives have spoken against the decision, and all parties are preparing for the provincial election in 2018. To ensure this minimum wage hike, real-life organizing—not Facebook posts and discussions—will be critical to bolstering the movement and ensuring that the promise isn’t rolled back by a successive government.

It’s not surprising that the most successful mobilizations have used Facebook peripherally. In Canada, no protest in the past four decades has come close to the size of impact of the 2012 Quebec student strikes against tuition increases. Student spokesperson Gabriel Nadeau-Dubois explores the debates that happened in cafeterias, school hallways and gymnasia across Montreal in his book, Tenir Tête: “[T]here was nothing spontaneous about the strike . . . it was, on the contrary, the fruit of a long and often taxing mobilization effort,” he writes. Despite the fact that social media occupied the same level of importance then as it does today, and that activists were young and of the generation best positioned to leverage Facebook, Nadeau-Dubois’ analysis barely mentions organizing on Facebook. While many protesters were on social media, the students took the time to meet face-to-face in order to gain their victory.

The strength of that movement can’t be overstated: it toppled the Liberal government of Jean Charest. Now, five years later, Nadeau-Dubois is sitting in the National Assembly, having recently won in a by-election with just under 70 percent of the vote, beating out twelve other candidates. (What was Nadeau-Dubois’ first statement as a sitting MNA? Calling on the government to heed the demands of Quebec’s own Fight for $15 campaign and implement a higher minimum wage.)

There are, of course, benefits to using Facebook. As the “I Stand With Gilary” campaign showed, the medium can be useful in micro-activism. But we have to be honest with ourselves about how damaging our overreliance on Facebook has become in the macro. If our desire for social change extends beyond the resolution of a single issue, we need to close our laptops, turn off our phones, and spend time in the presence of others. Building a better world requires meeting up and looking each other in the eye, and that means leaving Facebook behind.