In November 2011, Navaid Aziz received a phone call from a friend in Calgary who’d heard about a job opening there: a Muslim organization that ran a mosque and a downtown prayer space in the city had an opening for an imam, who would lead prayers and give sermons. Aziz, then a thirty-year-old lecturer and marriage counsellor active in Montreal’s Muslim community, went to Calgary for an interview a few weeks later. He didn’t bother asking why the previous imam had left. “I should have done that,” he says.

A few months later, Aziz took on the position at the Islamic Information Society of Calgary. After delivering his first Friday sermon, Aziz walked outside and mingled with the congregants. At six foot two, with the frame of a linebacker and a tireless smile, he’s hard to miss. As he squeezed through the crowd, he noticed a familiar face: Tamim Chowdhury, who had attended a seminar Aziz gave at the University of Windsor in 2008. When their eyes met outside the mosque that day in April 2012, Chowdhury looked away. Standing next to him was another young man, a white convert named Damian Clairmont.

Chowdhury and Clairmont were part of a tight-knit group of six friends who lived together above the downtown prayer space, known as the 8th and 8th Musallah. In the privacy of their apartment, they studied the biographies of the companions of the Prophet Muhammad, men who had lived in seventh-century Arabia. They also watched videos featuring Anwar al-Awlaki, the New Mexico–born preacher and Al Qaeda recruiter who had been killed by an American drone strike in Yemen six months earlier. In a warm but firm tone, Awlaki encouraged his viewers to make war on “unbelievers.” The United States–led invasion of Iraq and “continued US aggression against Muslims,” he argued, demanded jihad against America and its allies. It was the moral responsibility of every Muslim to join the fight, he said. Far from Calgary, a conflict still in its infancy was attracting tens of thousands to international jihad’s latest theatre of war: Syria.

Aziz often noticed the friends coming down from their apartment, whose lobby led directly into the 8th and 8th, to pray. They kept to themselves and didn’t interact with other congregants. Gradually, the group’s numbers grew smaller until no one from the apartment showed up for prayers anymore. Eventually, Aziz says, he began to understand why the mosque’s imams were leaving: “I realized that we had a problem with jihadists.”

In Calgary, Aziz found a Muslim community in conflict—and denial—over how to address the fact that dozens of young men were leaving their community to travel to distant battlefields. The Canadian government estimates that as of the end of 2015, 180 Canadians overseas were actively involved with terror organizations; about half of them are believed to be in Syria and Iraq, having been recruited by groups such as ISIS. It was difficult for members of the city’s Muslim community to accept that radicalization was happening in Calgary. It seemed implausible that these young men could be capable of carrying out acts of violence abroad—until it started happening.

Many in the community hoped that Aziz might be able to intervene. He was, after all, not much older than those who were leaving. Other imams in the community, most of them foreign born and middle-aged, had trouble connecting with Muslim youth born and raised in Canada. They didn’t know how to address political issues such as the conflict in Syria with those who were unsettled by the slaughter of thousands of civilians. Imams across the country feared that broaching the subject of overseas conflicts and jihad directly might draw objections from others in their mosques—or worse, attract the attention of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS).

After the six friends living above the 8th and 8th all left, Aziz settled into life in Calgary with his wife and two young daughters. In September 2012, on top of his duties at the mosque, he became the Muslim chaplain at the Southern Alberta Institute of Technology (SAIT), a polytechnic institute with 50,000 students. The work was slow. He held office hours twice a week for two hours, but was often alone, hoping someone would come in and talk with him. A few weeks into the semester, a student ran into his office and shut the door behind him. “I’m in trouble,” the young man said. “I stole money from some people, and they’re trying to kill me.” Aziz told him to calm down and invited him to sit. His name was Farah Shirdon, and he was a nineteen-year-old business student who was rediscovering Islam after a difficult few years.

Aziz told Shirdon that he should find an honest way to pay back his debts. In the weeks that followed, Aziz helped the young man find a job at the school. Soon Shirdon started coming to prayers on campus and to Aziz’s classes at the 8th and 8th. Sometimes he would drift back into his previous ways, but Aziz was always there, answering his calls at 4 a.m., ready to guide him. With Aziz’s support, Shirdon began applying himself in school more and reconnecting with his family. Islam, with its daily regimen of five prayers, was helping him find tranquility. “There were a lot of positive changes,” Aziz says, “but I think he wanted too much too quick, and that’s where the problems started.”

Instead of gently wading back into Islam, as Aziz advised, Shirdon jumped in headfirst. “I was very misguided, and Allah guided me. Went from the street life to the rug life,” Shirdon tweeted in June 2013, remembering those years. He had grown up loving rap and had memorized dozens of lyrics, but now he considered music to be haram—forbidden—along with movies, Facebook profile pictures, and democracy. He shunned alcohol and pot, as well as his old friends.

On Twitter, where he went by the name Abu Musa, he made new friends to replace the old ones. He became a popular figure, gaining more than 9,000 followers. In his profile picture, he wore a white cloth over his head; he would often copy and paste Islamic quotes—claiming them as his own and sharing them without attribution—creating the appearance that he was a learned scholar of Islam. His community on Twitter, mostly young Muslims living in Western nations, was fixated on the civil war in Syria. Together, they discussed the various rebel groups fighting against the Syrian regime of Bashar al-Assad and shared photos of children mutilated and killed by barrel-bomb explosions. Occasionally, Shirdon would mention the goal of establishing an Islamic caliphate or refer to jihad. In October 2013, Shirdon tweeted: “I remember I once told my father I want to go to Syria on the phone. He hung up.”

In the summer of 2014, Phil Gurski, a retired CSIS analyst, was in Windsor, Ontario, speaking at an Islamic community centre. As part of an outreach program run by Public Safety Canada, Gurski was travelling to Muslim communities across the country to share what he had learned about identifying signs of radicalization through his decades in intelligence. His work for CSIS relied on a strong rapport with Canadian Muslims, but the relationship between government agencies and the Muslim community had soured under the government of Stephen Harper.

In 2011, Harper declared that Canada’s biggest threat was “Islamicism.” The suggestion that Islam itself was a threat to national security was characteristic of the tone Harper and the members of his cabinet sometimes took with Canadian Muslims during the decade they were in power. “The Muslim community felt the Harper government wasn’t interested in talking to Canadian Muslims about issues, but just interested in investigations that lead to arrests and trials,” Gurski says.

Tactics such as the use of paid informants planted in mosques—what CSIS calls “human sources”—undermined the potential for co-operation and made many in the Muslim community feel that in the eyes of their government, they were a fifth column and so could not be trusted. Under Harper, it became harder to reach out to the Muslim community on security issues. “I saw myself as trying to help mend some fences and see if they would be willing to engage in the dialogue we used to have,” Gurski says.

During the Q&A following Gurski’s talk in Windsor, a young Muslim man stood up and accused him of Islamophobia and exaggerating the threat of terrorism. Others in the audience grew frustrated and told the man to sit down and shut up. Tensions escalated until Gurski stepped in to prevent a physical confrontation, and the young man left. Later, Gurski was approached by an attendee who apologized, saying, “Sorry about that—he’s our local extremist.”

Gurski learned that the man who had confronted him was named Mohammed El Shaer. In late 2013, Canadian media reported that El Shaer had been on a flight to Paris via Iceland in the company of Ahmad Waseem, another young man from Windsor, who was heading back to the front lines in Syria after recovering at home from an injury he’d received in battle. El Shaer returned to Canada and then left the country again in early 2015, despite being on a list of high-risk travellers. That night in Windsor in 2014, he served as a fitting example of what Gurski had been speaking about: individuals on the path of radicalization exhibit behaviours that are overt and easily identifiable.

As Gurski went across the country meeting imams and Muslim community leaders, something unexpected happened: he started making friends. Among them was a young imam who had recently moved to Calgary, Navaid Aziz. The imam was different from most Gurksi met. He was young and had been born and educated in Canada. “He’s very friendly and outgoing,” Gurski says, “which made it easy to have a conversation with him and see what he was trying to achieve.”

Gurski believes that interventions during the early stages of radicalization work best at the community level. When CSIS or the RCMP become involved, they do so to launch an investigation, not to convince an individual to give up a radical ideology. An imam such as Aziz, Gurski thought, would have a better chance than most in a community to intervene early. “But even with a guy like Navaid,” Gurksi says, “a person too far down the pathway of violent radicalization would reject him.”

Navaid Aziz was born in 1981 in Montreal to Muslim parents from India and Pakistan. He found his religious identity as a thirteen-year-old at a predominantly white high school: of the 2,000 students there, he was one of only fifty who came from an immigrant family. It wasn’t hard for him to spot a group of Muslim teenagers in the halls, and they soon became his close friends. Together, the boys played basketball, hockey, and video games, went to book club, and prayed at the mosque. Some of them took Arabic classes, which Aziz particularly enjoyed. He was eager to read the Quran in its original language.

Every weekend, Aziz took an hour-and-a-half bus ride from the South Shore to Saint-Laurent to get to class. Eventually, though, he began getting rides home with a friend who was old enough to drive. One day, Aziz’s friend had to make an important stop on the way: he had an interview with the Islamic University of Madinah, the Harvard of the Muslim world. The admissions interview was at a nearby mosque, and once they arrived, Aziz followed him inside. A man at the door with a clipboard asked Aziz for his name and phone number—he assumed they would be used to invite him to activities at the mosque. After he’d waited for his friend for half an hour, he heard someone call his name.

He was then beckoned into a side room, where a man asked him to recite some verses from the Quran, which he did, and asked him eighteen questions about Islamic jurisprudence, most of which Aziz got wrong. Then the man asked him for four pictures. Aziz asked him why. “You just applied to the Islamic University of Madinah,” he said. By accident, Aziz had interviewed for one of the most respected centres of Islamic learning in the world.

Nine months later, when he was eighteen, a beat-up letter arrived in the mail from Saudi Arabia. He was one of six students—out of the approximately 400 who had applied from Canada—who had been accepted to study at the university the following year. (His friend didn’t get in.) But Aziz didn’t want to go. He already had a scholarship to study management information systems at Concordia the following year. When his parents found the letter, they encouraged him to try the school for a year to see whether he liked it.

When Aziz arrived in Medina in 2000, he fell in love with the city. The second-holiest city in Islam after Mecca, and home to Muslims from all across the Middle East and South Asia, Medina was a lively metropolis of 1.2 million. Aziz had never lived in a city, or a country, where the majority of the inhabitants practised Islam. He could finally practise his faith and not be a second-class citizen, which is what he felt he’d been in Canada. It was his connection to Medina that convinced Aziz to stay at the university for seven years, during which time he completed an associate degree in Arabic literature and a bachelor’s in Islamic law.

When Aziz returned to Montreal after his studies, he did not find the prospect of a life spent leading prayers and giving sermons appealing. His local imam advised him of the biggest need in their Muslim community, so Aziz went back to school and received a certificate in marriage counselling. He worked as a family and marital counsellor for a few years while establishing himself as a popular public speaker. Since 2010, he has lectured thousands of times to Muslim audiences in dozens of countries.

When Aziz talks to young Muslims, he doesn’t focus on obscure Islamic theology. He’s practical and explores all aspects of their lives, from education and career to finances and family. He urges them to study subjects they’re passionate about and to earn as much money as they can—but only to help those who are disadvantaged. He tells them to travel the world and meet people different from them. For Aziz, Islam is as much about how one interacts with others as it is about personal faith. “Learn how to deal with others,” Aziz told a youth conference in Malaysia. “Empathize and sympathize and learn where others are coming from.”

Aziz became a rare entity in the Canadian Muslim community: a young imam born and raised in Canada who could connect with youth as easily on stage or on Twitter as he could in the mosque. Aziz’s affinity for young people made him an ideal candidate for the position in Calgary, which involved working with troubled youth in the community. But he arrived too late to help his former student Tamim Chowdhury or the friends living above the 8th and 8th Musallah.

One of those friends was Salman Ashrafi, a newly married analyst at an oil company, who went on to kill forty-six people and himself in a suicide bombing at an Iraqi military base in November 2013. Damian Clairmont was captured and killed by the Free Syrian Army in Aleppo in January 2014. Chowdhury outlived his compatriots: in August 2016, a month after orchestrating an attack that killed twenty-nine people at a café in his home country of Bangladesh—where he had become ISIS’s local leader—he was killed in a gunfight with a SWAT team at his hideout.

Every grim death abroad brought fresh scrutiny from the media and law enforcement and security agencies at home. As the imam of the mosque these men had prayed at and lived above, Aziz was often a target of attention. Canadian and international media began reporting in 2014 that Calgary was a “hotbed of terrorism” and claimed that the 8th and 8th was the centre of ISIS recruiting in the city.

The mosque was vandalized multiple times, and Aziz began receiving threatening emails and voicemails. “You have to consider Alberta when compared to other provinces,” Aziz says. “You’re already under suspicion for being brown, but now, as soon as you’re Muslim, it became ten times worse.” In one chilling voicemail left for Aziz at the mosque, an unknown man said, “We are going to come and rape all your women and mutilate them.”

It was in this climate that Aziz first met Farah Shirdon, the business student who burst into his office and said he owed money to gangsters. Like Aziz, Shirdon was the son of immigrants: he was born in Toronto on April 18, 1993, to Muslim parents who’d come to Canada because of the security and opportunities it could offer their children. But his father, Mohamed, ended up leaving the country to find work, and so Shirdon spent his childhood years in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

As a teenager—after his mother, Nura, moved the family to Calgary’s residential Cedarbrae neighbourhood—Shirdon enrolled in John Ware Middle School. There, he stuck out because he was tall and black, but he didn’t have any trouble fitting in. He had never been particularly interested in his family’s roots in Somalia, where one of his uncles had served as prime minister from 2012 to 2013. When his mother tried to convince him to learn Somali, he’d refuse, saying that he felt Canadian and didn’t need to learn another language.

Towards the end of high school, Shirdon was expelled for fighting and charged with assault. That surprised his friends and family, who had never thought of him as violent or a bully. “He wasn’t a badass or a tough kid,” says Jason White, who worked alongside Shirdon for three years at a local movie theatre, which gave Shirdon his first job. White, his team leader, remembers him as a hard worker who always showed up on time and was constantly entertaining. “He always wanted to be famous,” White says. “He used to tell people that he was going to be on TV one day.”

At Lord Beaverbrook High School, where Shirdon transferred after the fight, he tried shedding his image as the class clown. “He was known as funny and goofy,” says Harmen Khara, a friend from that time, “and then he started getting all fucked up at parties and dealing weed.” Shirdon would use his six-foot-two stature to intimidate other dealers, mugging them on the streets of Calgary for drugs. After he had been arrested three times in two years, his parents grew concerned about the direction his life was taking. They told him that if he didn’t change, he would have to leave their house and face life on his own as a nineteen-year-old on probation.

Shortly after this ultimatum, Shirdon’s interest in Islam was ignited during a family trip to Saudi Arabia after graduation. When he returned to Calgary, he began distancing himself from drugs, alcohol, and close friends. Some found this new, pious Farah arrogant and self-righteous. But Shirdon didn’t care: he had repented and was moving on. “I was a messed-up guy and into some crazy things,” Shirdon later wrote online. “Islam changed me and it will change you too if you turn to Allah wholeheartedly!”

In the fall of 2012, Shirdon began a two-year business diploma at SAIT, where he would say his prayers between classes in a small interfaith meditation room within view of the Muslim chaplain’s office. Aziz had just started as chaplain and was becoming a mentor and a friend to a number of young Muslims on campus. For Shirdon— from the moment he ran into Aziz’s office—Aziz became a role model; Shirdon began visiting the imam multiple times each week on campus and at the mosque, where he attended his classes.

“From the time I started working with him, the gang criminality stopped,” Aziz says. “He was coming to the mosque more frequently, praying, and taking his life more seriously.” When Aziz told him that he had attended the Islamic University of Madinah, Shirdon asked, “How do I get in?” Aziz helped him with the online application. Shirdon now had a new plan: finish his business studies, then go study Islam in Saudi Arabia, just like his mentor.

Every three months, Aziz gave a workshop for young Muslims who wanted to learn how to deliver khutbahs, or public sermons. The khutbah, which is delivered during noon prayers on Fridays, is the main occasion for formal public preaching in Islam. During the workshop, Aziz told the attendees to keep their audiences engaged by sharing stories with dramatic details. Shirdon, a confident public speaker who loved being in front of crowds, was keen to try. After the first session, he asked Aziz, “When can I start giving khutbah at the 8th and 8th?” Aziz told him he needed to be patient. “Keep attending my workshops, and then we’ll find a place for you to give khutbah,” he told him.

On a Friday soon after, around 100 Muslim students gathered in the gymnasium at SAIT for noon prayers. Shirdon ignored Aziz’s advice to wait, and asked the Muslim Student Association whether he could deliver the khutbah. Shirdon stood up at the front and began talking in a slow and dramatic voice about the suffering of civilians in Syria. He became louder and more emotional when he spoke about the violence and death being visited upon innocent Sunni Muslims. Shirdon thought there was someone to blame. “We need to get those rafidi Shia kuffar,” Shirdon said to the crowd. Because he had been speaking for so long, some students missed the fact that he had used a derogatory term for Shia Muslims—but many Shia students raised their heads in confusion.

Eemaan Khan, the president of the Muslim Student Association, heard the offensive remark but remained silent, as custom demanded. Khutbahs have no official time limit, but on campus, they rarely ran longer than ten minutes; Shirdon’s was now pushing thirty. Khan had to motion to Shirdon to wind up the proceedings, because students needed to go to class. Afterwards, Khan approached him to explain that what he had said was offensive and didn’t make sense. Shirdon apologized and told him that he had been reconnecting with Islam and had briefly been in a gang before “finding the light.” He opened up to Khan and told him that his father lived in Saudi Arabia, while his mother travelled back and forth.

Shortly after meeting him, Khan started following Shirdon on Twitter; he soon noticed a “colossal disconnect” between his online identity and the Farah Shirdon he knew. “He had this online Twitter persona as if he actually knew what he was talking about,” Khan says. Online, Shirdon shared derogatory comments about Shias similar to the one he had made during his khutbah. One day after class, Khan called Shirdon, and the two began arguing about the content of his speech. After thirty minutes, Shirdon reluctantly apologized and hung up. He then blocked Khan on Twitter. “Everybody just thought he was one of those guys just coming into religion,” Khan says. “No one fully knew what he was.”

Shirdon became close friends with Mohammad Khan (no relation to Eemaan), a fellow Muslim student at SAIT a few years older than he was. “Farah and I just connected,” Khan says. “He was a big guy, but very gentle.” Shirdon wouldn’t discuss his past, but he frequently mentioned Syria. They agreed that Muslims weren’t doing enough to help. Shirdon talked about donating food and clothing, and brought up doing relief work in refugee camps. “But then it transformed into ‘We should fight,’” Khan says. At the time, ISIS had not declared a caliphate—it would do so in June 2014—or begun executing Westerners on camera.

Muslim community leaders and prominent scholars had not yet ruled on the legitimacy of rebel groups fighting against the Syrian regime, though many radical preachers, their voices amplified by the Internet, were calling for jihad. Shirdon was confused. “The information he had was that these guys are bringing back Islam, they are taking down dictatorships, they are fighting to help the Syrian kids,” Khan says. “And then you have videos of Syrian kids being blown up. Who’s not going to get upset?”

During a car ride from Calgary to Edmonton to attend a lecture by an Islamic scholar, Shirdon asked his friend whether he could play an audio lecture. “The entire world is standing against one ritual of Islam,” the voice said through the speakers, “and that is jihad.” The lecture was long and went into detail about religious justifications for violence. Khan asked who the lecturer was. “Anwar al-Awlaki,” Shirdon replied. Khan hadn’t heard of the Al Qaeda recruiter, but he was alarmed. He encouraged his friend to finish his business diploma and pursue his plan to study Islam in Saudi Arabia. “My argument was ‘You don’t know what is going on; you don’t know if ISIS are the good guys or the bad guys,’” Khan says. “What are you going to do?”

After 9/11, CSIS shifted its focus from the espionage activities of foreign governments to terrorism. A 2002 report by the Security and Intelligence Review Committee, the independent watchdog that reviews CSIS’s operations, noted that recent history “teaches us that public opinion driven by scandals or calamitous events can profoundly affect how security intelligence bodies carry out their tasks.”

A decade later, CSIS introduced a set of designations to label individuals they were investigating: sympathizer, supporter, extremist, terrorist. A sympathizer is someone who may be “inclined” toward a certain organization or cause, but is not willing to financially or physically support it. A supporter—one step above—is willing to offer funds and propaganda assistance to the group or ideology, but is still averse to offering his own body. An extremist may attempt to convert others to his views or incite them to violence, and a terrorist is one who “has or will” engage in an act of politically or religiously motivated violence.

Agents use these definitions to rank their open investigations, but determining who might graduate from “sympathizer” or “supporter” to something else is a near-impossible task. Monitoring the online accounts of targets is resource intensive, and most individuals who reveal extremist views on social media will not become violent or join terror groups. Agents therefore devote resources to investigating people who appear radical but never end up taking action.

In January 2013, Shirdon tweeted: “I wonder how many fake FBI & CIA monitored accounts are following me?” Shirdon’s tweeting alone checked a number of disturbing boxes for intelligence agents and raised suspicion at CSIS. For example, he praised extremist preachers such as Anwar al-Awlaki. “WHAT AN INTELLECT & they called him a terrorist,” Shirdon wrote.

He also communicated directly with Ahmad Musa Jibril, a radical cleric from Dearborn, Michigan, who had been banned from two mosques in the state because of his extremist views. There was nothing to prevent him, though, from preaching to Shirdon from a digital pulpit. In his lectures, Jibril advocates a version of Islam that praises war and bloodshed in the name of religion, although he doesn’t directly call upon his followers to join groups such as ISIS. Instead, he praises those who engage in jihad and compares the conflict in Syria to battles from the early days of Islam. “He’s like my role model,” Shirdon wrote of Jibril in 2013. “The only true scholar in the west.”

As Shirdon grew more isolated from his social circle in real life, he became more attached to his online community. On Twitter, he was rarely challenged on his opinions, and when he was, he could block whoever disagreed with him. It was on Twitter that Shirdon connected with Iftekhar Jaman, a young man who left England for Syria in May 2013. Jaman didn’t cut off contact with old friends such as Shirdon when he arrived; instead, he updated them daily with pictures and messages. Jaman described his life there as a “5 star jihad.” He said hundreds of foreign fighters from the West were given food, shelter, and a weekly allowance. In September 2013, Jaman tweeted, “Any brother hoping to come, then come. Alone or with a group. Both are good. No money is required when you come. The path is open now.”

For Shirdon, witnessing in real time Jaman’s experience of travelling to Syria and joining the fight against the Syrian regime was transformational. “Pays 1000s of dollars to attend university, sits watching YouTube vids all class,” wrote Shirdon. “Smh [shaking my head] time to drop out and head to #Syria!”

By the end of 2013, Shirdon’s resolve to leave was crystallizing. Jaman had recently been killed in battle, triggering an outpouring of online admiration from Shirdon and his friends: their fallen comrade was a martyr. Shirdon tried to establish a new contact with ISIS, eventually connecting with Jaman’s cousin, Abu Abdullah al-Britani.

When Aziz returned to Calgary from a trip to Malaysia in December, he noticed a change in Shirdon. He still came to his classes at the 8th and 8th, but he now engaged more in debate. He challenged Aziz on everything and began questioning the authority of Muslim scholars in the West who didn’t support jihad in Syria. When he approached Aziz with questions, they now had a different tone. “What do you think about the Khalifa? What do you think about ISIS?” Shirdon probed. He asked Aziz about the extremist preachers—such as Anwar al-Awlaki—he had been watching. “Let’s take it step by step, and we can answer these questions,” Aziz told him. Shirdon lashed out, calling him a “coconut imam.” To Shirdon, Aziz was brown on the outside, white on the inside, with an approach to Islam that was aimed at pacifying the West. It was the last time Aziz would see Shirdon.

When CSIS begins investigating an individual whose online views indicate radicalization, the agency sometimes employs a tactic called disruption. It is a simple idea: agents visit the individual they are investigating and tell him they know what he is up to. “Either they scare the shit out of you, or make you realize this is a bad idea,” says Phil Gurski. It does, though, have the potential to backfire by emboldening or spooking individuals into action. “For a lot of these guys, being visited by CSIS is a badge of honour,” Gurski says. “It gives them credibility where credibility isn’t really there.” A visit from agents of the government often confirms their belief that Western governments are hostile to Islam.

In early March 2014, Shirdon received a call at home from a CSIS agent. She asked whether they could meet at a café and talk. On March 9, Shirdon met the agent at a downtown Tim Hortons; his friend Mohammad Khan sat nearby, having already been questioned himself. For forty minutes, while patrons sipped coffee and ate doughnuts, the agent asked Shirdon about his thoughts on terrorism and whether he planned to leave the country. She brought up Shirdon’s online posts, and he tried to soften their appearance. “He just said what CSIS wanted to hear,” Khan says. “He thought they were idiots.” After the meeting, Shirdon told Khan he was worried they might take his passport away.

Three days after the meeting with CSIS, Shirdon used two credit cards to pay for contact lenses, a pair of glasses, and an Air Canada ticket to Istanbul for a flight two days later. He told his older sister, Idil—whom he lived with at the family home and who was his only relative still in Calgary—that he would be staying with friends over the weekend and not to expect him. On March 14, while Idil was getting ready for work, her brother came home unexpectedly in the middle of the day. He said he had forgotten his wallet and then quickly left.

A few hours later, Shirdon arrived at Calgary International Airport with one suitcase and boarded his plane, which made a stop in Frankfurt before landing in Istanbul on March 15. From Istanbul, he went to Akçakale, a small Turkish town on the border with Syria, where he got in touch with his contact, Abu Abdullah al-Britani, who would vouch for him once he crossed over. While waiting for the go-ahead, Shirdon called his mother in Saudi Arabia. He told her he was in Turkey and going to live in a Muslim country. “Why, why?” she asked him repeatedly. “I’m sorry, don’t be sad,” he said, before the phone abruptly disconnected. His mother called his sister in Calgary, and she went and checked her brother’s room. Everything looked the same, except all his clothes were gone.

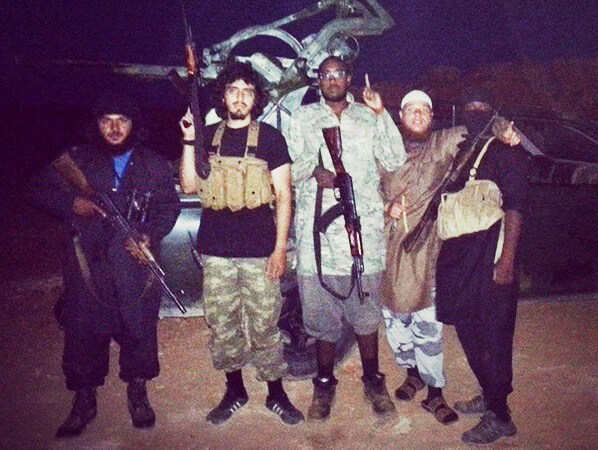

A month after Shirdon left, Aziz was in his office scanning through ISIS propaganda videos online as part of his research into radicalization. He came across a video of twenty young men standing outdoors in three rows. Each held an AK-47. A small fire burned at their feet. Most faces were obscured by balaclavas. Five minutes into the video, a young man dressed in black and camouflage and holding a Canadian passport began speaking calmly in English: “This is a message to Canada and to all the American tawagheet [tyrants]: we are coming, and we will destroy you.”

Aziz recognized him immediately. The man continued, his voice becoming more agitated: “I left comfort for one reason alone, for Allah. And inshallah [God willing], after Sham [Syria], after Iraq, after Jazeera [the Arabian Peninsula], we are going for you, Barack Obama!” With the others around him cheering and shouting “Allahu akbar,” Shirdon tore his Canadian passport into pieces, placed them in the fire, and stamped on them. The video was released a little more than a month after Shirdon’s meeting with the CSIS agent at the Calgary Tim Hortons.

The sight of Shirdon in the video shattered Aziz. For more than two years, Aziz had helped the young man find his way back to his faith. Now his former student was threatening violence against the West and using that same religion as justification. After news reports had identified Shirdon as the speaker in the video, Aziz posted a message on Facebook: “I was born in Canada and have lived here for most of my life . . . While I believe paradise to be my true home, the closest thing I have to one here on this earth is Canada . . . I hope you can now understand why I am greatly upset by this silly individual who travelled to Syria, burns his Canadian passport and threatens to come back and cause destruction.”

Officers from the Alberta division of the Integrated National Security Enforcement Teams (INSET), an anti-terror squad formed in 2002 in response to 9/11, learned about Shirdon’s whereabouts from the passport-burning video. On April 17, they interviewed Shirdon’s mother, who had flown back to Calgary from Saudi Arabia a week earlier, and his sister, the last person from the family to have seen him. His mother told police that they’d had no clue he was planning to leave, claiming that no one could have predicted his behaviour and that he must have been brainwashed. He was supposed to have graduated the next month with his business diploma, she said. Shirdon’s sister said that her brother had attempted to grow a beard, but otherwise hadn’t changed much. She mentioned he had attended the 8th and 8th—a name that officers were now well acquainted with.

Police investigators interviewed a number of Farah’s old friends, including Mohammad and Eemaan Khan, but they didn’t approach Aziz. Two CSIS agents did. They asked him questions about his relationship with Shirdon and mentioned that they had spoken to Shirdon five days before he left. “If you spoke to him, why didn’t you stop him from leaving?” Aziz asked. “We didn’t know he was planning on leaving,” one of them responded.

“Farah must have had a deadline of travelling to Syria, and it wasn’t March,” Aziz says. “He brought his date forward after he was visited by CSIS.” Aziz doesn’t believe that the agents understood the potential ramifications of their actions when they contacted Shirdon and met with him. “If I’d had more time, I could have possibly helped him.”

“I left Twitter to come back and see the same brothers tweeting about Jihad 24/7. Isn’t it time to stop tweeting and make Hijra [immigrate]?” Shirdon was back on Twitter again after his initial training camp finished in mid-April. He had retired the name Abu Musa and now went by Abu Usamah; he quickly gained 20,000 followers on his new account—more than he had ever had before.

Instead of tweeting about jihad from his bedroom or classroom in Calgary, Shirdon now tweeted from the front lines of Syria and Iraq. He wrote of the liberation of towns and of conflicts with groups such as the Free Syrian Army and Jabhat al-Nusra—now Jabhat Fatah al-Sham—which had a common enemy in Assad. He encouraged others to “run to the land of Jihad” and during Ramadan asked Allah to grant him his wish of martyrdom. When asked by a Vice reporter about his active Twitter account, he replied, “What’s the benefit of using social media if I’m not using it to recruit?”

On June 30, Shirdon said he was outside Al-Bab, a city northeast of Aleppo, where “the murtadeen (non-believers) were so afraid all we had to do was walk in for them to flee like cowards.” The day before, ISIS had crucified nine men in Al-Bab. Over the summer, the organization expanded its grip, moving into territories north and west of Mosul in an offensive that drove tens of thousands of Iraqi Christians and Yazidis from their homes. Shirdon’s Twitter activity faded. In August, a number of pro-ISIS Twitter accounts reported that he had been killed. His brother Liban, looking for answers about his sibling’s fate, reached out to some of the Twitter users celebrating his martyrdom. “I’m his little brother,” he tweeted. “How do you know for sure.”

Shirdon was in Barwana, in the Anbar province of Iraq, facing off against Iraqi troops. When he attempted to retreat, though, the truck carrying him and seven other people drove over an IED. He posted to his Instagram account in mid-September that he had been injured but was now recovering. Twitter had suspended his account, but he reappeared under a different username. “Twitter wishes to silence our media presence to ensure Muslims don’t wake up to the truth,” he wrote.

Shortly thereafter, his former high-school friend Harmen Khara was invited to join a WhatsApp messaging group with two existing members—one of whom was Shirdon, who wanted to know what people back home were saying about him. He was reading media reports and was annoyed that an estranged friend was giving interviews to newspapers and acting as if he knew him.

Shirdon sent them pictures of himself holding guns. Khara challenged him on the violence being spread by ISIS, but Shirdon said it was just propaganda intended to discredit the group. “What about cutting people’s heads off and putting it on the Internet?” Khara wrote. Those were prisoners of war, Shirdon replied. He told his old friends that he would soon be interviewed by Vice. On September 23, Shirdon appeared on Skype wearing a black hood over his head. He told Vice co-founder Shane Smith that he was in Mosul, Iraq.

“A lot of brothers, they’re mobilizing right now,” Shirdon told Smith, alluding to attacks planned for the US. He mentioned the meeting he’d had with CSIS before he left Canada. “I can’t believe how someone that has extremist, terrorist ideologies is sitting in front of you, and you didn’t capture them,” Shirdon said. The Vice interview received millions of views, and Shirdon’s threats made headlines and news reports around the world. “He always loved attention,” Khara says.

That fall, at the mosque in Calgary, Aziz noticed a new face in one of his classes. He later learned that the well-spoken and intelligent young man was Farah’s younger brother, Liban. Aziz was surprised that he hadn’t introduced himself. “Dude, why didn’t you tell me you were Farah’s brother?” he asked him. “There’s so much I want to know. Did you know what was going on?” Liban said that the family had been aware that he had changed, but hadn’t understood what that meant.

One day after Friday prayers, Liban started shouting at Aziz, angry that the imam had given interviews about his brother on television the previous day. “You have no right speaking about me and my family,” Liban said. “Everything I’ve said is truthful,” Aziz responded. Aziz offered to act as a facilitator between the family and the media so they could share their side of the story. Liban said he would get back to him, but never did.

Six months later, the police finally visited Aziz. It seemed strange to him, given his close relationship with his former student, that officers had waited so long to approach him. For months, police had been investigating Aziz to see whether he was the notorious recruiter whose existence was rumoured by the media. They said that Shirdon’s mother had told police that the only person who could have radicalized her son was Aziz. He was speechless. He told them that as an imam, he had an open-door policy and talked to everyone from drugs addicts to young men with criminal pasts. “If you had a concern about me, why not come and speak to me?” Aziz asked. They told him they were just doing their job. Police found no evidence against him.

In the months after Shirdon left, Aziz stopped travelling as much and focused more on the needs of his community at home. Although his mosque was traditional and served mostly as a place for prayers and sermons, Aziz realized it had to evolve. “All we did was teach youth how to read Quran,” he says. In 2015, he began a youth mentoring group to draw on what he had learned from his relationship with Shirdon. The group serves as a safe space where young Muslims can talk openly about their grievances against Western foreign policy in the Middle East and Islamophobia in the West—two root causes of radicalization that are often ignored. “When the activity is pre-criminal, let’s see what we can do to help these individuals first,” Aziz says.

The group revolves around service and study. Participants are encouraged to feel confident about their Muslim identities and to acknowledge their duty to serve all people. The youth in the program volunteer at homeless shelters, clean up the city, plant trees, and spend time with seniors at retirement homes. They learn about the life of Prophet Muhammad and his companions, and also about the lives and teachings of Gandhi, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King Jr. “Youth end up joining ISIS because of built-up frustration over injustices they see in the world,” Aziz says. “They feel marginalized themselves, and ISIS claims they are going to fight oppression. That’s where it starts.”

There was an uproar in the Calgary Muslim community when it heard Aziz was initially going to accept only six participants for the program. Many parents approached him about enrolling their own children. “I was forced to expand to twelve, and that’s where we’re at now,” he says. The youngest participant is seventeen, and the oldest is twenty-eight. So far, two have graduated. “By graduating, I tell them they’re mature enough to take care of themselves, but I’ll still be here to help you,” he says.

A year after the program’s founding, police approached Aziz and asked whether they could recommend youth they were concerned about for the group. Aziz agreed. He also consulted with police on the development of ReDirect, a Calgary police initiative launched in September 2015 to help youth at risk of radicalization. Three months later, the Calgary Police Service appointed Aziz as its first Muslim chaplain. The same department that had investigated him on suspicion of radicalizing youth in the community now comes to his mosque for diversity training.

After Shirdon left Canada, an envelope arrived at his home with an acceptance letter from the Islamic University of Madinah. He was one of sixteen students in the country to be accepted for the 2015 year. Aziz had talked to his contacts there, and played a part in helping Shirdon get in. The same month Shirdon would have begun his studies, the RCMP laid six charges against him in absentia, including “participation in the activities of a terrorist group,” using as evidence the violent and threatening statements he had made on social media and in interviews. The last time he called his mother, he told her he didn’t want to break ties with the family. He also had news: he was married now. He gave the phone to his wife, a young British Somali woman, so she could speak to her mother-in-law.

A week after terrorism charges were brought against Shirdon, Aziz flew to Kelowna, BC, where for the first time he lectured on “misconceptions about Islam” to a majority non-Muslim audience. When he saw the packed lecture hall on the campus of the University of British Columbia Okanagan, he grew nervous.

“It’s very important to distinguish between what a faith is, and what its followers try to represent,” Aziz told the audience. “Somewhere along the line, disconnects happen. People do things for the wrong reasons under a particular name.” Aziz brought up words that are often misunderstood by non-Muslims, including sharia and jihad. The term jihad comes from the word mujahada, meaning “to struggle,” he said, and the first mention of jihad in the Quran is in the context of struggling against ignorance. “When ignorance is prevalent in the world,” Aziz continued, “the first step to eradicating it is to enlighten people with knowledge.” This was true jihad, Aziz said. This was his jihad.

This appeared in the January/February 2017 issue.