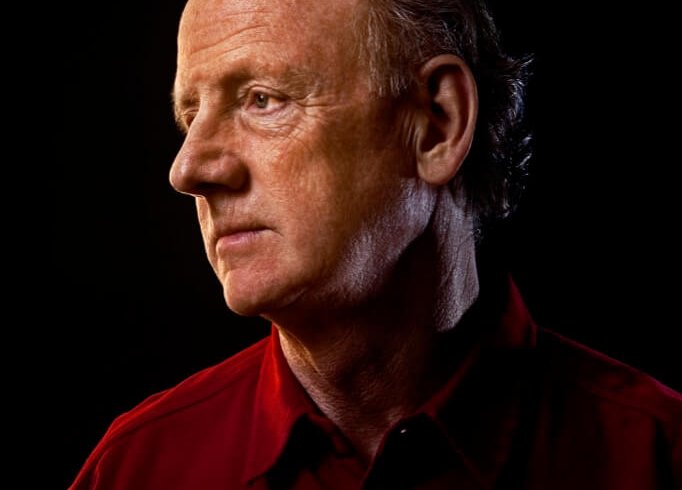

Every year, on the second Sunday after Labour Day, the village of Eden Mills, Ontario, hosts a writers’ festival. Readings take place on lawns and fields next to the sleepy waters of the Eramosa River. The 1,800 paying visitors—readers, writers, people on the fringes of the arts—are a casually dressed, somewhat counterculture bunch. Usually, the only discordant note in this bucolic scene is the uniformed soldiers of the Wellington Rifles Volunteers, who administer parking and first aid. But in 2009, a second anomalous sight appeared, in the shape of a tall man dressed in bright yellow slacks worn high to reveal purple socks. His electric blue dress shirt glaring in the sunlight, John Ralston Saul stood out from both the bohemian crowd ambling down the village’s main street and the soldiers along its edges; yet he is alien to neither. His life bridges Canada’s arts community and its military and government institutions. The distinctive outlook he has developed by spanning these two worlds is central to his vision of culture, industry, and government in Canada and the world, and has inspired a career that, one month later, in October 2009, would see him become the first Canadian to be elected president of International PEN, the organization that campaigns for freedom of speech for writers around the world, and whose past presidents have included such literary heavyweights as John Galsworthy, Arthur Miller, Heinrich Böll, and Mario Vargas Llosa.

Saul turns off the main street and walks down a path that leads past the brick-and-clapboard-clad Eden Mills Community Hall into a clearing in the trees. This is the Adisokaun Site, the festival’s most controversial locale. Bypassed by most festival-goers, it was set up in 2002 to offer First Nations writers, storytellers, and drummers a venue in which to show off their talents without being subjected to the demanding selection procedure that determines invitations to the festival. Depending on your point of view, the Adisokaun Site is either a shining example of affirmative action or the artistic equivalent of an Indian reservation. In recent years, two First Nations writers have complained of being denied access to the festival’s mainstream audience after being obliged to read in the woods. On the strength of his book A Fair Country, which argues that aboriginal heritage has a significant influence on daily life in Canada, Saul has become the first non-native writer to be invited to the site. (Unlike most First Nations writers, however, Saul will also read later in the day, at a mainstream festival location.) His appearance at the Adisokaun Site is announced as a dialogue, but the conversation doesn’t go well. His host, an aboriginal comic and writer named Drew Hayden Taylor, reels out corny one-liners that deflate Saul’s points before he can develop them. The crowd, uneasy about trespassing on “native land,” hangs back on the edge of the clearing. Finally, Saul interrupts his host to invite everyone to come closer. He asks those who have brought deck chairs to move them to the front of the clearing. His voice is both authoritative and peevish. He waves his hands, urging Canadians from disparate backgrounds to come together, because he has something important to tell them.

In John Ralston Saul’s confidence that he can speak to all Canadians lies the core of his public personality. It’s also why we find him unnerving, and why media coverage of the man displays scorn as often as it does admiration. His emergence as the most articulate public custodian of national values our leaders seem to disdain has done little to alleviate this uneasiness. Most Canadians identify fiercely with their region, yet find the idea of Canada elusively abstract. Many of us feel secretly guilty about responding to other regions with stereotypes or resentments—at not being better coast-to-coast-to-coast Canadians. Saul aggravates this subliminal guilt because he has no obvious regional identification and has an apparently effortless relationship with the nation called Canada. If we feel reprimanded by Saul’s existence, if he appears to glide through an ether that floats slightly above the plane of daily life, this may be the reason. In social situations, Canadians place one another by region in the way that Americans define new acquaintances by where they went to college. Once you learn that the other person is an Albertan, a Québécois, a Newfoundlander, you know who you’re dealing with; a Canadian who lacks a regional identification elicits feelings of mistrust. Yet that is Saul’s heritage.

The Armed Forces, as Prime Minister Stephen Harper recognized in placing them at the centre of the Conservatives’ vision of Canadian identity, constitute one of our few authentically national institutions. Saul was born into a military family in 1947. His father, Colonel William Saul, was a first-generation soldier; his mother’s family had a long tradition of military service. Saul’s older brother, who married an Englishwoman, served as an officer in the British Army. From the beginning, Saul’s life took place in a national context. Born in Ottawa, he was christened in Calgary. He spent his infancy in Alberta and much of his childhood in Manitoba, and graduated from high school in Oakville, Ontario. As a young man, he became fluent in French. By the time he started university at McGill, his father was working in Paris and Brussels as a military adviser to the Canadian ambassador to NATO. John was accepted into the foreign service and appeared destined for a life of diligent diplomacy. But William Saul’s sudden death from an aneurysm in 1968—he was forty-nine—changed his son’s plans. Turning down the foreign service, John left Montreal to attend graduate school at King’s College, London. His doctoral research took him to Paris, where his career as a writer began.

It is fascinating to speculate that the death of his father released John Saul from establishment conformism, although his writing, as though in homage to his parents, has championed their world: a national vision of Canada supplemented by the insights offered by Parisian and French culture. Yet the self-confident spokesman on Canadian identity and international politics did not emerge naturally from Saul’s public service background. Military officers implement policies; they don’t analyze or reimagine them. If they criticize governments, their criticisms are judiciously phrased and for internal consumption only. To become a provocative public intellectual, and in particular a self-defined Canadian public intellectual, Saul had to undertake a lengthy process of self-reconstruction.

After settling in France, where he supported himself by running the French subsidiary of a British investment company, he also had to find his way home. In Europe, he came to resemble Mavis Gallant’s characterization of Canadians who, after years abroad, can no longer admit who they are: “Sometimes they try to pass for British, not too successfully, or for someone vaguely chic and transatlantic. I have wondered, but not wanted to ask, how they replace the national sense of self.” In Saul’s case, the national sense of self was displaced by a voracious expertise on French politics. His doctoral thesis, “The Evolution of Civil-Military Relations in France after the Algerian War,” received a chilly reception from the examiners at King’s College, effectively ruling out an academic career and adding a new layer to his personality: a disdain of “mediocre frightened academics.” The 653-page thesis—which examined the death of French president Charles de Gaulle’s chief of staff, General Charles Ailleret, in a plane crash in 1968—plumbed the inner workings of the French bureaucracy. Determined to publicize his theory that Ailleret had been assassinated, Saul rewrote his research as a novel.

Published in French in 1977 as Mort d’un général, with the names of the historical figures changed, and later in English as The Birds of Prey, with the names restored, the novel rode the coattails of Frederick Forsyth’s The Day of the Jackal, one of the biggest bestsellers of the 1970s, which dramatized an assassination attempt on de Gaulle himself. A spare, almost emotionless novel that reads as though it had been translated from the French, The Birds of Prey sold over a million copies. The dedication—“to / Charles de Gaulle / from a disciple / Sans peur / et / Sans regret”—stakes out Saul’s position as an opponent of the young leftists who supported the May 1968 Paris student revolts de Gaulle suppressed. The novel’s opening pages ridicule the stock figure of “a young American student, apparently unclean, leafing through pages of defunct socialist monthlies.” It is instructive to find the criticisms of bureaucrats and courtiers in Voltaire’s Bastards and The Unconscious Civilization foreshadowed by the conspirators in The Birds of Prey; but it is startling to glimpse Saul’s later Canadian nationalism, often characterized by his critics as left wing, being nourished by de Gaulle’s centralization of the Fifth Republic.

The Birds of Prey exposes a personal identity crisis. The protagonist, Charles Stone, is a cipher: an aimless, independently wealthy, bilingual young anglophone living in Paris. He carries an Irish passport but is not Irish. He seems to be one of Gallant’s Canadians, trying to pass “for someone vaguely chic and transatlantic.” Stone is the creation of a writer who is trying to work out how to forge a public personality from a surface of urbane ambiguity. The description of the protagonist could apply to his creator: “Stone was a tall man… His strength was deceivingly hidden because his lines were smooth and clean as if he were slight. His character appeared in the same way, deceptively hiding in its own good balance.”

By the time The Birds of Prey was published, Saul had returned to Canada. David Mitchell, a banker who had taught him in a management seminar in New York, mentioned his name to Canadian businessman and United Nations official Maurice Strong. In 1976, when Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau appointed Strong to found Petro-Canada, Saul became the new director’s executive assistant. Strong later characterized Saul as “an invaluable, though unconventional, member of my personal staff.” Saul’s readjustment to Canada after seven years in London and Paris was not easy. As Strong recalled, “At times he caused me some problems with other members of our growing team, whose toes he frequently stepped on. His manner and lifestyle were those of a cultured aristocrat, which made him something of an eccentric in Calgary. He soon became known in the local restaurants for his fastidious taste, which few if any of Calgary’s establishments were able to satisfy.”

Between 1976 and 1978, while working in the oil business, Saul began to travel widely. He also met Adrienne Clarkson. The latter event facilitated the former: by entering into a life partnership with a woman who was an established public personality and eight years his senior—he was twenty-nine, she thirty-seven with children from her first marriage—he confirmed that his life would be devoted to the pursuit of career rather than to founding a family. As John Lownsbrough wrote of the couple in 1994, “Each seems to understand and encourage the other’s need for independent travel.”

Saul made his first trip to Asia at the behest of Pierre Trudeau and Fidel Castro. The new Communist government of Vietnam asked Castro for advice on managing the oil concessions it had inherited from its capitalist predecessors. Castro requested help from Trudeau, who dispatched Strong to Vietnam. As the negotiations were to take place in French, Strong invited Saul to accompany him. This trip to Hanoi—a destination at that time off limits to most Western passport holders—appears in fictionalized form in the opening scene of Baraka, the initial novel in the Field trilogy, published between 1983 and 1988, which formed the foundation of the first incarnation of Saul’s public personality. After leaving Petro-Canada, and particularly between 1982 and 1987, when Clarkson served as Ontario’s agent general in France, he roamed northern Africa and Southeast Asia from his base in Paris. A journey with the Shan guerrillas in Burma supplemented his earlier travels with the Polisario Front in the Western Sahara. He promoted himself as a writer in the tradition of Joseph Conrad, Graham Greene, and V.S. Naipaul, who brought home to the West the chaos and violence of the world it had colonized. Lacking the points of intimate connection with impoverished societies afforded by Conrad’s Polish childhood, Greene’s Catholicism, or Naipaul’s Indo-Caribbean background, Saul took a more analytical approach. In Baraka, which describes a plot by American oil executives to sell weapons abandoned by the US Army in Vietnam, the detail with which he renders his settings is compelling; the people are less persuasive. Hard-nosed oilmen make such remarks as “The fatal errors of life come from men being logical, not unreasonable. The States is dying from logic applied like religion, whereas it should be the slave of well-intentioned men.”

As the trilogy progressed, a theme that is discussed nowhere in its pages came to the fore: the problem of speaking as a Canadian in the international sphere. The three central characters in Baraka are Americans who met as students at McGill. Their Canadian friend, the dissolute journalist John Field, has lived in Bangkok since his early twenties. Field has a walk-on role in Baraka; is a minor character in The Next Best Thing, where the protagonist is British; and takes the lead in The Paradise Eater, the best of the three novels, which won a literary prize in Italy. The Americans in Baraka never come to life: Saul’s attempts to evoke the Chicago childhood of Laing, the most sympathetic of the group, feel forced. The portrait of Spenser, the British art collector in The Next Best Thing, benefits from Saul’s longer experience of London; like his creator, Spenser has a father who dies of an aneurysm.

The Paradise Eater, in which Field takes the lead, feels like the work of a writer coming to grips with his themes. His groin rotting from venereal diseases acquired in the brothels of Bangkok, Field personifies unconscious Western savagery; the narrator tells us that he has never set foot in the civilizing realm of Europe. The first two novels are about journeys. The Paradise Eater focuses on Bangkok, depicted as a repository of Western decadence. Repeated images of the city threatening to sink beneath flood waters reinforce the theme of moral collapse. Field’s working-class Anglo Montreal background, his friendship with a Québécois UN worker, his father’s fascination with the Rocky Mountains, all ring true. Targeted by murderous drug smugglers, he must finally accept that Bangkok is not his home. The trilogy concludes with him on his way to Calgary, staring at a photograph of his late father standing in the Rockies.

Saul, too, needed to come home. The Field trilogy earned him many readers but denied him the critical respect he sought. His populist attacks, denouncing “highly literate” writers such as John Updike, Saul Bellow, and Philip Roth as “degenerate,” did not help. As the Cold War wound down, his pose as a colonial adventurer came to seem antiquated, offensive, or faintly ludicrous. A 1986 Globe and Mail profile by Margaret Cannon concluded with the observation that “Saul radiates the imperial insouciance his fictional characters lack. If there’s an outpost to be found, he’ll be there, impeccably dressed and discussing the degenerate West.” A publicity photo for The Paradise Eater showed him in a colonial slouch hat. His uncomprehending evocation of female characters—major plot twists in each of the first two Field novels depend on happily married women impulsively committing adultery—grated on an increasingly feminized culture. Discussing adolescent prostitution in Bangkok with interviewer Nancy Wigston in 1988, Saul echoed a character in The Paradise Eater by stating that “the problem with Western girls is that they don’t have orgasms because they don’t screw young enough.”

It was time for a makeover. When Clarkson’s appointment in Paris ended, the couple moved to Toronto. Saul served as vice-president in 1989–1990 and president from 1990 to 1992 of the Canadian chapter of International PEN. It was the first step in a startlingly successful reinvention of both his writing and his public persona.

“It’s taken me thirty years to get to what I wrote in A Fair Country,” Saul says. It is December 2009, two months after his election as president of International PEN, and the sumptuous 785-seat mainstage of the River Run Centre in Guelph, Ontario, is almost sold out. Saul is giving the annual Guelph Lecture on Being Canadian. Next to him onstage, at his request, stands a chair that holds a portrait of the imprisoned Burmese poet Zargana. Saul’s appearance is sober: a pale blue pinstriped dress shirt open at the neck, a navy blue jacket, and grey slacks that are too long to reveal the colour of his socks. He lectures in a soft voice in which the keening high notes have been muted. When he gestures to emphasize his points, his hands, gyrating palm up and far out to the sides of his body, look as though they are scooping a solid substance out of the air. He knows his script—recasting Canada as “a civilization that looks like a Western civilization but is oral”—by heart, yet he departs from his text to make impassioned asides on issues ranging from the rise in homelessness to the complicity of higher education in weakening Canadian identity: “Universities are the most organized structure we have for training people to think that this country doesn’t exist.”

The retooling of Saul’s image, from an elegant throwback of popular fiction to a focused, substantial public intellectual, was achieved in one fell swoop with the publication of Voltaire’s Bastards in 1992. The book’s international success dispatched him on a speaking tour that has continued, more or less unabated, for eighteen years. Appearing in the same year as Francis Fukuyama’s triumphalist tract The End of History and the Last Man, which exulted that with the fall of the Berlin Wall American models would reign supreme forever, Voltaire’s Bastards punctured an unseemly euphoria about Western infallibility. Saul’s 640-page archaeology of the evolution of the Western model is bathed in a scathing skepticism. The core of his argument is that reason, a necessary tool for Enlightenment dissidents such as Voltaire (who were struggling for equality and individual rights against an order characterized by monarchic privileges and ingrained religious dogma), has been transmuted into inflexible management doctrines that are economically wasteful and anti-democratic. The book appealed to the first cohort to feel uneasy about the emerging world of globalization.

Specialists picked holes in the details of his arguments, yet Voltaire’s Bastards, like Jared Diamond’s Collapse, is one of those popular “big think” books that make an impact on public debate despite their inconsistencies. Most important for Saul, the book, which illustrates its points by interweaving American, British, French, and Canadian examples, enabled him to find a voice in which to address international debates from an unselfconsciously Canadian perspective. His later works, which would look both outward to the world and inward to Canada, are a series of refinements of arguments broached in Voltaire’s Bastards. This is most obvious in the 1995 CBC Massey Lectures, The Unconscious Civilization, which extends the Voltairean metaphor by attacking managers as the “courtiers” of the contemporary world; and in the satirical mock encyclopedia The Doubter’s Companion. But it is true even of his engagement in such projects as the Institute for Canadian Citizenship, of which he is co-chair; French for the Future, which he founded in 1997; the short biographies of Penguin Canada’s Extraordinary Canadians series, which he conceived and edits; and the LaFontaine-Baldwin Lectures, which bring together Canadians from both official language groups with aboriginal or foreign intellectuals. What all of these undertakings have in common is the assumption that an informed citizenry is the only defence against an elite estranged from history and the common good by the destructive doctrines of “rational management.”

The strongest evidence of John Saul’s commitment to refashioning his image is his decision to suppress his fifth novel in English. De si bons Américains (Some Good Americans) was published in France in 1994 and reprinted in 2001; it has not appeared anywhere else. Given that his previous novel, The Paradise Eater, appeared in eleven countries and won a major international prize, it seems implausible that he couldn’t find publishers for this book. De si bons Américains is a charming, readable novel-in-stories that might have done credit to W. Somerset Maugham; but, combining social elitism with Third World tourism, it epitomizes the image that had become a burden to Saul. The narrator is a wealthy American based in France, the kind of person who flies from Europe to Mexico for the weekend to attend a high society party. His gossipy tales of his super-rich friends are interspersed with a series of chapters entitled “Conversations with Dictators,” in which the narrator meets Moroccan strongmen, Mauritanian coup plotters, and Haitian dictator Baby Doc Duvalier. The juxtaposition of Western decadence with foreign tyranny comes to a head in the novella-length chapter “A Good American,” in which the narrator is exposed as the core of the problem. In an exclusive London club, he meets a man who tells him that an extended prank the narrator played as a youth drove the man’s father to suicide: “You’re so degenerate, you Americans. Always sermonizing, sermonizing everybody, but you live in a cesspool.”

Sentiments such as these, though they go down well in France, risked reviving the criticisms attracted by the Field trilogy and undercutting the weightier reputation Saul was gaining as a cultural critic. The constitutional crises and free trade debates of the late 1980s and early 1990s drew him into Canadian arguments. De si bons Américains was a detour on his road home. During the mid-1990s, as Canadian institutions shuddered before the implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement, Saul wrote Reflections of a Siamese Twin: Canada at the End of the Twentieth Century, an extended first draft of his vision of the country. In the context of the 1990s, he contended, “rational management” translated into economic continentalism and the warring, equally blinkered compartmentalization of the “Oui” and “Non” sides in the 1995 Quebec referendum, each of which condemned the other’s nation as “not a real country.” Canada, he insisted, had been built on moderation, “complexity,” and social justice achieved by constant communication across lines of cultural difference. This flexible polity, rather than tariff barriers, was what NAFTA was attacking. The treaty’s goal “was not free trade. We already as good as had that. Rather it was the rejection of enforceable social standards in favour of a nineteenth-century—now known as neo-conservative—theory.”

Reflections of a Siamese Twin signalled a realignment in Saul’s thinking. His assertion that the United States was “the natural prolongation of the European idea” marked the end of his fraught love affair with Europe. No longer the source of civilized reprimands to American “degeneracy,” Europe now became, far more problematically, the point of origin of the monolithic, unilingual, managerial state that served as a model for the United States. Canada, he argued, differed from this European/US model in having been built on cross-cultural collaboration. French settlers in the seventeenth century learned how to survive the winter from the aboriginal people; francophones and anglophones worked together for democratic government. Refuting Québécois nationalist mythology, Saul stresses that Louis-Joseph Papineau in Lower Canada and William Lyon Mackenzie in Upper Canada were in close contact during and after the Rebellions of 1837. Their thwarted collaboration bore fruit with the coordination of Louis-Hippolyte LaFontaine and Robert Baldwin, whose ministries of 1842–43 and 1848–51 created the first democratic government in any European colony.

There is nothing original in this reading; many of us were taught in high school about LaFontaine and Baldwin uniting the country by running for election in each other’s ridings. But Saul’s assertion that Canada works only when moderate reformers meet across cultural, regional, and linguistic lines results in some dissident interpretations. The First World War, often touted as our “coming of age,” becomes “a great division that almost destroyed Canada”: 60,000 dead, a Parliament with French and English seated on opposite sides of the House, anti-conscription riots in Quebec City, and a ban on teaching in French in Ontario. Depicting the discourse of jingoistic nationalism and that of corporate management doctrine as sharing common roots, dogmatisms, and exclusions, Saul brandishes LaFontaine and Baldwin to refute Lucien Bouchard and Brian Mulroney.

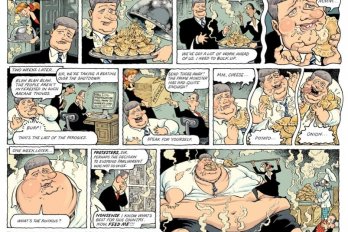

Saul’s sallies against NAFTA earned him the disdain of the neo-conservative right. On September 9, 1999, the National Post announced Adrienne Clarkson’s appointment as Governor General with the eccentric headline “Activists Move into Rideau Hall.” As the first anglophone male consort to a Governor General, Saul was often portrayed as emasculated, his writing denigrated. A month after Clarkson’s appointment was announced, the Ottawa Citizen ran a profile of him with the headline “Intellectual Fraud Parades as Genius.” Stephen Harper, then president of the National Citizens’ Coalition, said, “Saul is such an intellectual lightweight that a ten-kilometre wind would blow him right off the ground.”

From the first article written, from the first story,” Saul told journalism students at King’s College, Halifax, in 2004, “you will discover whether you have the willpower to stand your ground.” The subject of his talk was the nineteenth-century Nova Scotian journalist and political leader Joseph Howe’s defence of freedom of speech. Saul’s passion for this issue, which is not always popular on the left, suggests that while his rage at the dismantling of national institutions may run parallel to left-wing critiques on such points as support for public education and the social safety net, it has different origins and goals. During his inaugural address as president of International PEN in Linz, Austria, in October 2009, he went out of his way to attack Cuba for denying liberty of expression. A shadow of the animosity displayed by the narrator of The Birds of Prey toward the socialist student in the library persists. The “good balance” of the novel’s protagonist, Charles Stone, is now writ large in its author’s quest for a society based on “equilibrium” and “fairness.”

Saul has refined his expression of these values. Voltaire’s Bastards, Reflections of a Siamese Twin, and On Equilibrium are highly original, yet uneven, books. The Collapse of Globalism, which charts how countries such as New Zealand and Malaysia won back their inclusive, “positive nationalist” equality and autonomy after suffering under the free trade dogmas of managerial elites, is more tightly focused. A Fair Country is equally crisp. Written in an almost flat, conversational style that reads like a conscious refutation of specialized managerial jargon, A Fair Country makes startling claims: that Canada is primarily an oral culture; that it is the least “Western” of Western nations; that our first elites were mixed-race families founded by fur traders who married chiefs’ daughters, and that present-day cross-cultural marriages of immigrants and their children are an extension of this “métis” tradition; that our penchant for peacekeeping has roots in aboriginal ways of dealing with conflict; that even our preference for single-tier health care derives from the aboriginal dictum of “eating from a common bowl.” It’s difficult not to feel skepticism before some of these claims. But as Saul outlines his conclusions to the packed house in Guelph, one can feel the audience’s doubts receding: his concrete examples lend far-reaching assertions an aura of inevitability.

Why is he doing this? His schedule is crammed with talks all over Canada, in addition to his foreign speaking engagements. The endless tour, like his other projects promoting Canadian history and citizenship, stems from his urge to expose our ineffectual leaders, whose neglect is eating away at the solid foundations Canadian society inherited from four centuries of creative fair-mindedness. Listening to John Saul talk about the indigenous heritage, about LaFontaine and Baldwin, you might be surprised to learn that nearly half of A Fair Country is devoted to savaging “the castrati”: our hapless political and business leaders. This is the theme that concentrates his energy and anger. The descendant of selfless servants of the nation, he is outraged that Canada’s leaders disdain our historical traditions. His descriptions of how, with the implementation of free trade, a residual colonial mentality has fused with market doctrines to induce “self-loathing” among our decision-making classes are lethal precisely because they feel so accurate.

His solution for reviving our faltering institutions is a culture of collaboration, enshrined in a “métis civilization” inspired by the aboriginal heritage. With their booming demographics and increasingly adept leadership, aboriginal Canadians represent a rising social force. Saul maintains that they are also our classical culture: he sees the words of the nineteenth-century chiefs Big Bear and Poundmaker as a “Canadian version of a Greek chorus.” He is not the first nationalist intellectual to respond to the looming shadow of the United States by strengthening his hand through alliances with the indigenous past. In 1891, the Cuban poet José Martí, warning of the approaching “seven-league boots” of American power, proclaimed the pre-Columbian civilizations of the Americas “our own Greece.”

But do aboriginals want to be the point of origin of Saul’s métis civilization? Last year, participating on a panel in Toronto, I was surprised by the vehemence with which urbanized, racially mixed aboriginal intellectuals, who did not speak their ancestral languages, rejected all suggestions that they might belong to a hybridized culture, asserting their identity in terms of a cultural and racial purity of the sort that Saul rejects. Here, too, history offers a lesson. In the 1960s, liberal Anglo-Canadian nationalists tried to associate themselves with the breaking wave of Québécois radicalism, only to feel jilted when it became clear that the Québécois elite wanted to build their own country rather than make ours more diverse. Today’s aboriginal activism may disillusion its non-aboriginal promoters in the same way. Still, John Ralston Saul, tirelessly signing books after his talk in Guelph, snow swirling around the limousine that waits to whisk him back to Toronto, insists that to be Canadian is to have been shaped by the aboriginal heritage. After a long road home, he has discovered his Canada. As president of International PEN, he will travel the world. Wherever he goes, his métis civilization will accompany him.