The white-gloved handler leads you through locked doors with his pass card, into rooms where the lights blink on as you enter. He holds up the comic book so you can see it. No touching. The same rules apply to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, stored nearby.

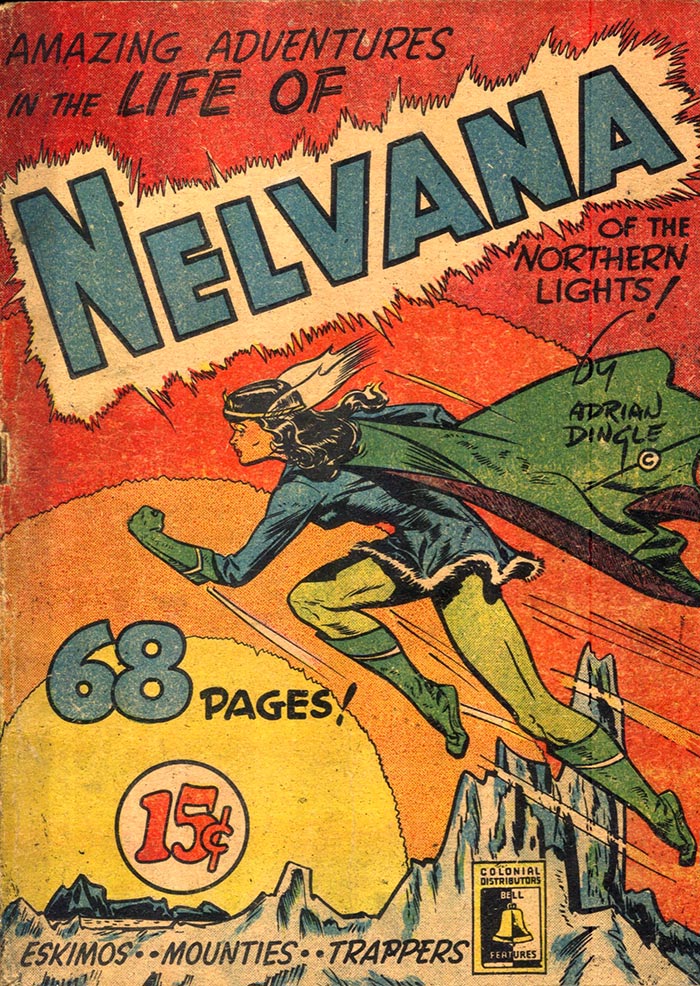

In Gatineau, Quebec, deep beneath the Library and Archives Canada Preservation Centre, more than 3,000 homegrown comics are preserved inside these climate-controlled vaults. One gem, Triumph-Adventure Comics number one, debuts Nelvana of the Northern Lights, an Inuit demigoddess who travels on a beam of the aurora borealis. Loosely based on an Arctic legend that the writer and illustrator Adrian Dingle heard from Group of Seven co-founder Franz Johnston, Nelvana is drawn in black and white and dressed in a cape, long sleeves, knee-high boots, and a fur-trimmed miniskirt.

Published in August 1941, she predates Wonder Woman by three months. Your patriotically minded but nerdy comic book friends may have already told you this. And this: while Wonder Woman originals fetch anywhere from $4,800 to $100,000, you could theoretically purchase a number one Nelvana for as little as $1,000—if you could find one. Fewer than five copies still exist.

Filmmaker Will Pascoe resurrects the story of Nelvana and dozens of other forgotten Canadian superheroes in Lost Heroes, a 107-minute documentary that will air on Super Channel in March. During World War II, the War Exchange Conservation Act restricted trade of non-essential goods between Canada and the United States, an act of protectionism that inadvertently gave rise to the golden age of Canadian comics.

To meet the new demand, a handful of publishers began churning out black and white comics, soon dubbed “Canadian Whites” for their cost-saving monochrome, but the comics lacked colour in other ways, too. Nelvana rescues geologists and conserves fish supplies. Johnny Canuck, an Allied air force captain, is praised by Winston Churchill and slugs Hitler. Canada Jack’s bland, generic superpower takes the form of all-around athleticism. He aids the young members of his own fan club when their bikes are stolen, and when enemy forces derail their plans to fundraise for war savings stamps. Perhaps most memorably, he investigates the theft of a coin collection, only to discover that a blue jay is the culprit.

Canadian kids may have embraced these comics because they had nothing else to read, and when the act was repealed in 1946 and full-colour American superheroes flooded the market the Whites faded away. Our publishers couldn’t match their southern competitors’ deep pockets, or their lower printing and shipping costs. The characters’ distinct regionalism may have been another factor. While American artists and audiences project America onto any backdrop (think New York in the guise of Gotham), Canadians tend to douse their heroes in poutine gravy and give them beavers for sidekicks. And they wonder why their creations are marginalized.

Pascoe hopes the digital age will breathe new life into our forgotten comics, this time by opening borders rather than protecting them. After all, publishing online is so cheap and easy. He notes that crowd sourcing has already funded True Patriot, a graphic anthology of homegrown heroes, as well as a newly animated Captain Canuck web series, and a Nelvana reprint announced on October 1.

Still, a global audience will be less interested in Canadian stories than in well-told ones. Who wants to read about Canada Jack accosting a blue jay while Superman is busy saving Metropolis from Lex Luthor’s deadly atomic beam? Benjamin Woo, a post-doctoral fellow at the University of Calgary who wrote his master’s thesis on national identity in comics, suggests that it is time to let go of the quest for a patriotic superhero. We need to “celebrate the cultural production that does exist, that is vital and interesting and a key part of the whole field of comics,” says Woo (who used to call himself Dr. Nerd on his website).

He points to Stuart Immonen, the Canadian who has illustrated All-New X-Men, Ultimate Spider-Man, and New Avengers. Jeff Lemire’s Essex County trilogy, set in southwestern Ontario, has been nominated for awards here and in the US. Chester Brown’s biographical comics, including Louis Riel, have earned critical acclaim. So have Seth’s graphic novels Clyde Fans and George Sprott (1894–1975). And in 2010, Universal Pictures distributed the film adaptation of Bryan Lee O’Malley’s Scott Pilgrim series, about a slacker musician living in Toronto.

Even Pascoe, who plans to celebrate the release of his documentary by purchasing a Nelvana, sees the appeal in a superhero like the Alberta-born Wolverine (Canadian by birth only). Superman’s Metropolis skyline was modelled on Toronto’s, and plenty of books put out by American comic giants DC and Marvel are written and illustrated by Canadian creators. Our superheroes may not sport maple leaf motifs, but that doesn’t mean they are lost. You just need to read between the speech bubbles to find them.

This appeared in the January/February 2014 issue.